29 January 2026 · Articles

29 January 2026 · Articles

Applying behavioural design to help people make more sustainable choices

Learn how to apply behavioural science techniques to change habits and drive the adoption of more sustainable actions. In this article, we focus on how our practice is integrating learnings from behavioural sciences to address the climate emergency.

We strongly believe that achieving sustainable outcomes requires a deep understanding of people’s behaviour and a careful consideration of how services and products can be designed to encourage sustainable choices

Why do we integrate behaviour science in design work?

Combining behavioural science insights and design is becoming well-established. This is evidenced by the many resources available and the growing number of case studies across diverse industries, including healthcare, finance and education where behavioural science has contributed to a deeper understanding of the factors that influence human behaviour, such as social norms and habits. Pressed by the increasing urgency to address the climate emergency, the design industry has also seen a rise in the number of projects aimed at driving sustainable behaviours forward.

“Affecting behaviour change can be as simple as providing an incentive, but it can also require a complex combination of different strategies. Behavioural and social science frameworks help designers understand and analyse the motivations and barriers that their target actors have relative to behaviour change. They also help to design effective interventions.”

– Katie Williamson, Philipe M. Bujold and Erik Thulin (2020)

When and how do we apply behaviour change?

From discovery to definition, design and delivery – there are multiple opportunities to integrate behavioural science in our design practice.

Discover

To design for sustainable behaviour change, designers must first understand the current behaviour and the drivers behind it. This requires designers to extend established qualitative research methods with models and frameworks from the behaviour sciences to reveal insights into people’s behaviour and the factors that influence it.

User research tools like observation, interviews, and diary studies can all be used to study behaviours and identify barriers to behaviour change. For example, if we want to reduce plastic waste, we need to identify the behaviours that contribute to this problem, such as using single-use plastic bags or disposable cups and target these behaviours for change.

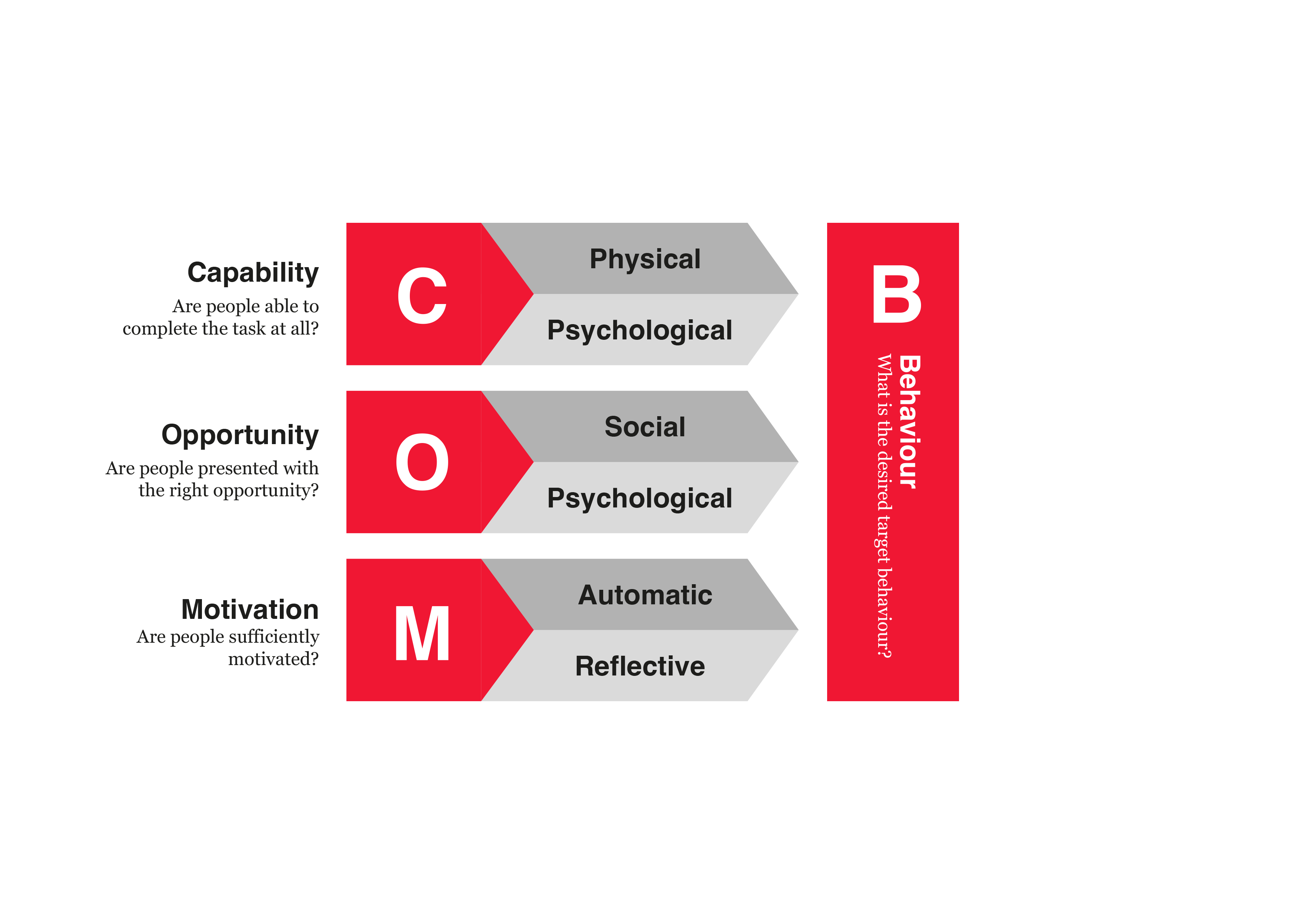

Behaviour change models and frameworks, such as COM-B and the Behaviour Change Wheel, however, allow designers to take a structured approach to identifying barriers to behaviour change during user research and help designers frame interventions to overcome them. The COM-B model describes how behaviour change (B) requires a balance between three factors:

- Capability (C):knowledge and skills

- Opportunity (O):environmental and social factors

- Motivation (M):beliefs and emotions

Building on the previous example, let’s say we want to encourage people to use reusable coffee cups instead of disposable ones. We can use the COM-B model to identify the barriers and enablers of this behaviour. We might find that individuals lack knowledge about the environmental impact of disposable cups, that social norms favour convenience over sustainability, and that the physical environment does not facilitate the use of reusable cups.

Define

Building on the insights gained from research and the application of behaviour change models and frameworks, designers can develop a hypothesis for behaviour change. This hypothesis should outline the target behaviour, the key factors that influence the behaviour, and the intervention strategies that are most likely to be effective in changing behaviour. For this purpose, it’s useful to have a ‘zoomed out’ approach so we can see that behaviour change is part of a larger system of activities.

Service design tools can help visualise the touchpoints in that system that are most influential in driving behaviour, so that designers can orchestrate interventions that address them.

For example, we might use journey maps to identify the areas of opportunity for design, such as when people order their coffee or dispose of their cup. In a similar way, system maps can help us understand the feedback loops that reinforce a certain behaviour and the nodes that can be leveraged to produce change (we’re going to expand on this topic in a future blog of this series).

Design

Once designers have identified the most influential factors that impact behaviour change, they can eventually develop targeted interventions that address them.

Well-framed brainstorming sessions can provide an invaluable source of ideas at different points in the journey and discussion can help the team prioritise the most viable or impactful solutions.

Popular levers for behaviour change in the literature include gamification, social incentives, and data visualisation to increase awareness, provide relevant information and ultimately encourage the adoption of the target behaviour.

Finally, teams can use prototyping to test and refine interventions before launching them.

By understanding people’s behaviour and the drivers behind it, designers can develop interventions that address the barriers and enablers of behaviour change. With the increasing urgency to address the climate emergency, it is more important than ever to integrate these techniques in our practice and drive the adoption of more sustainable actions.

Reflecting on key tensions between Design and Behavioural Science

When it comes to behaviour change design, tensions can arise between the practices of behavioural science and service design. Our teams have identified three areas where these tensions can manifest: mindset, approach, and language.

In terms of mindset, behavioural scientists often favour narrowing down on a specific behaviour change intervention early in a project as this helps robust measurement and evaluation of behaviour change.

However, as service designers our design practice encourages divergent thinking, rapid framing and re-framing of problems as we seek to understand the barriers to behaviour change and reflect on a broad range of possible interventions. Therefore, when working across the two disciplines it is important to establish early-on shared expectations regarding how behavioural interventions will be designed and evaluated.

Regarding approach, behavioural science guides us to predict the impact of behaviour change interventions and establish evaluation criteria in advance. One way to achieve this is by creating a Theory of Change. Service Designers are also often comfortable with working hypotheses and using prototypes to test assumptions, especially in Government. However, their hypothesis testing typically occurs within an iterative design process, where prototypes are employed to rapidly learn and refine designs.

Service designers should also consider the broader impact of a design intervention, not just on a user’s behaviour but also on the larger system in which the change is implemented. This requires zooming in and out to analyse the effects on both the user and the overall system. In our upcoming articles on Systems Thinking and Futures Thinking, we will delve into exploring these concepts further, including the identification of unintended consequences.

The final tension we want to focus on is the use of language. If we take the word “concept” for example, it holds different meanings depending on whether we approach it from a science-based or design-based perspective. In these cases, we’ve found adopting a visual approach, such as using service mapping and storytelling tools, can help multidisciplinary teams create shared understanding. Similarly, designers who incorporate behaviour change models and frameworks may not fully understand the subtle differences between various models and may mistakenly attempt to use them interchangeably.

It’s crucial for designers and behaviour scientists to have mutual respect for each other’s disciplines, and to remain open-minded to expanding their understanding of each other’s craft. We believe that identifying, understanding and managing tensions like these can help designers combine behavioural science in their practice more effectively.

Would you like to know more about behavioural design?

At NEC Digital Studio, we are committed to designing for people and planet. That’s why we have designed a practical course delivered remotely over two half days called Designing for Behaviour Change. It’s a space to learn more about taking a user-centred approach to behaviour change design – what it is, how it works and how it can add value for reframing problems and considering environments and sustainability.